The purpose of this document is to present how IP Fragmentation and Path Maximum Transmission Unit Discovery (PMTUD) work and to discuss some scenarios involving the behavior of PMTUD when combined with different combinations of IP tunnels. The current widespread use of IP tunnels in the Internet has brought the problems involving IP Fragmentation and PMTUD to the forefront.

The IP protocol was designed for use on a wide variety of transmission links. Although the maximum length of an IP datagram is 64K, most transmission links enforce a smaller maximum packet length limit, called a MTU. The value of the MTU depends on the type of the transmission link. The design of IP accommodates MTU differences by allowing routers to fragment IP datagrams as necessary. The receiving station is responsible for reassembling the fragments back into the original full size IP datagram.

IP fragmentation involves breaking a datagram into a number of pieces that can be reassembled later. The IP source, destination, identification, total length, and fragment offset fields, along with the "more fragments" and "don't fragment" flags in the IP header, are used for IP fragmentation and reassembly. For more information about the mechanics of IP fragmentation and reassembly, please see

RFC 791

.

The image below depicts the layout of an IP header.

The identification is 16 bits and is a value assigned by the sender of an IP datagram to aid in reassembling the fragments of a datagram.

The fragment offset is 13 bits and indicates where a fragment belongs in the original IP datagram. This value is a multiple of eight bytes.

In the flags field of the IP header, there are three bits for control flags. It is important to note that the "don't fragment" (DF) bit plays a central role in PMTUD because it determines whether or not a packet is allowed to be fragmented.

Bit 0 is reserved, and is always set to 0. Bit 1 is the DF bit (0 = "may fragment," 1 = "don't fragment"). Bit 2 is the MF bit (0 = "last fragment," 1 = "more fragments").

| Value | Bit 0 Reserved | Bit 1 DF | Bit 2 MF |

|---|

| 0 | 0 | May | Last |

| 1 | 0 | Do not | More |

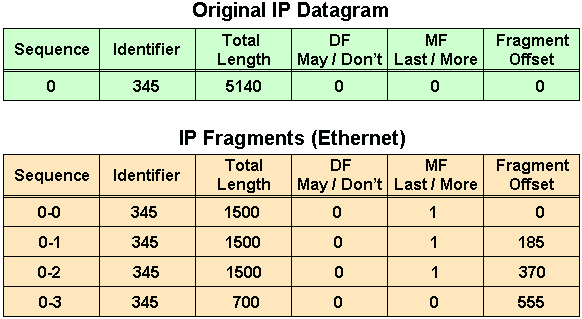

The graphic below shows an example of fragmentation. If you add up all the lengths of the IP fragments, the value exceeds the original IP datagram length by 60. The reason that the overall length is increased by 60 is because three additional IP headers were created, one for each fragment after the first fragment.

The first fragment has an offset of 0, the length of this fragment is 1500; this includes 20 bytes for the slightly modified original IP header.

The second fragment has an offset of 185 (185 x 8 = 1480), which means that the data portion of this fragment starts 1480 bytes into the original IP datagram. The length of this fragment is 1500; this includes the additional IP header created for this fragment.

The third fragment has an offset of 370 (370 x 8 = 2960), which means that the data portion of this fragment starts 2960 bytes into the original IP datagram. The length of this fragment is 1500; this includes the additional IP header created for this fragment.

The fourth fragment has an offset of 555 (555 x 8 = 4440), which means that the data portion of this fragment starts 4440 bytes into the original IP datagram. The length of this fragment is 700 bytes; this includes the additional IP header created for this fragment.

It is only when the last fragment is received that the size of the original IP datagram can be determined.

The fragment offset in the last fragment (555) gives a data offset of 4440 bytes into the original IP datagram. If you then add the data bytes from the last fragment (680 = 700 - 20), that gives you 5120 bytes, which is the data portion of the original IP datagram. Then, adding 20 bytes for an IP header equals the size of the original IP datagram (4440 + 680 + 20 = 5140).

There are several issues that make IP fragmentation undesirable. There is a small increase in CPU and memory overhead to fragment an IP datagram. This holds true for the sender as well as for a router in the path between a sender and a receiver. Creating fragments simply involves creating fragment headers and copying the original datagram into the fragments. This can be done fairly efficiently because all the information needed to create the fragments is immediately available.

Fragmentation causes more overhead for the receiver when reassembling the fragments because the receiver must allocate memory for the arriving fragments and coalesce them back into one datagram after all of the fragments are received. Reassembly on a host is not considered a problem because the host has the time and memory resources to devote to this task.

But, reassembly is very inefficient on a router whose primary job is to forward packets as quickly as possible. A router is not designed to hold on to packets for any length of time. Also a router doing reassembly chooses the largest buffer available (18K) with which to work because it has no way of knowing the size of the original IP packet until the last fragment is received.

Another fragmentation issue involves handling dropped fragments. If one fragment of an IP datagram is dropped, then the entire original IP datagram must be resent, and it will also be fragmented. You see an example of this with Network File System (NFS). NFS, by default, has a read and write block size of 8192, so a NFS IP/UDP datagram will be approximately 8500 bytes (including NFS, UDP, and IP headers). A sending station connected to an Ethernet (MTU 1500) will have to fragment the 8500 byte datagram into six pieces; five 1500 byte fragments and one 1100 byte fragment. If any of the six fragments is dropped because of a congested link, the complete original datagram will have to be retransmitted, which means that six more fragments will have to be created. If this link drops one in six packets, then the odds are low that any NFS data can be transferred over this link, since at least one IP fragment would be dropped from each NFS 8500 byte original IP datagram.

Firewalls that filter or manipulate packets based on Layer 4 (L4) through Layer 7 (L7) information in the packet may have trouble processing IP fragments correctly. If the IP fragments are out of order, a firewall may block the non-initial fragments because they do not carry the information that would match the packet filter. This would mean that the original IP datagram could not be reassembled by the receiving host. If the firewall is configured to allow non-initial fragments with insufficient information to properly match the filter, then a non-initial fragment attack through the firewall could occur. Also, some network devices (such as Content Switch Engines) direct packets based on L4 through L7 information, and if a packet spans multiple fragments, then the device may have trouble enforcing its policies.

The TCP Maximum Segment Size (MSS) defines the maximum amount of data

that a host is willing to accept in a single TCP/IP datagram. This TCP/IP

datagram may be fragmented at the IP layer. The MSS value is sent as a TCP

header option only in TCP SYN segments. Each side of a TCP connection reports

its MSS value to the other side. Contrary to popular belief, the MSS value is

not negotiated between hosts. The sending host is required to limit the size of

data in a single TCP segment to a value less than or equal to the MSS reported

by the receiving host.

Originally, MSS meant how big a buffer (greater than or equal to

65496K) was allocated on a receiving station to be able to store the TCP data

contained within a single IP datagram. MSS was the maximum segment (chunk) of

data that the TCP receiver was willing to accept. This TCP segment could be as

large as 64K (the maximum IP datagram size) and it could be fragmented at the

IP layer in order to be transmitted across the network to the receiving host.

The receiving host would reassemble the IP datagram before it handed the

complete TCP segment to the TCP layer.

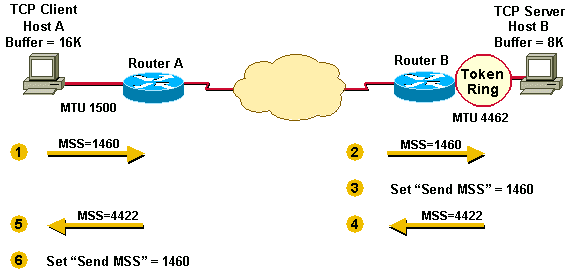

Below are a couple of scenarios showing how MSS values are set and used

to limit TCP segment sizes, and therefore, IP datagram sizes.

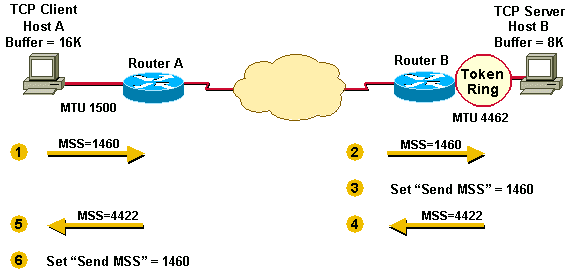

Scenario 1 illustrates the way MSS was first implemented. Host A has a

buffer of 16K and Host B a buffer of 8K. They send and receive their MSS values

and adjust their send MSS for sending data to each other. Notice that Host A

and Host B will have to fragment the IP datagrams that are larger than the

interface MTU but still less than the send MSS because the TCP stack could pass

16K or 8K bytes of data down the stack to IP. In Host B's case, packets could

be fragmented twice, once to get onto the Token Ring LAN and again to get onto

the Ethernet LAN.

-

Host A sends its MSS value of 16K to Host B.

-

Host B receives the 16K MSS value from Host A.

-

Host B sets its send MSS value to 16K.

-

Host B sends its MSS value of 8K to Host A.

-

Host A receives the 8K MSS value from Host B.

-

Host A sets its send MSS value to 8K.

In order to assist in avoiding IP fragmentation at the endpoints of the

TCP connection, the selection of the MSS value was changed to the minimum

buffer size and the MTU of the outgoing interface (- 40). MSS numbers are 40

bytes smaller than MTU numbers because MSS is just the TCP data size, which

does not include the 20 byte IP header and the 20 byte TCP header. MSS is based

on default header sizes; the sender stack must subtract the appropriate values

for the IP header and the TCP header depending on what TCP or IP options are

being used.

The way MSS now works is that each host will first compare its outgoing

interface MTU with its own buffer and choose the lowest value as the MSS to

send. The hosts will then compare the MSS size received against their own

interface MTU and again choose the lower of the two values.

Scenario 2 illustrates this additional step taken by the sender to

avoid fragmentation on the local and remote wires. Notice how the MTU of the

outgoing interface is taken into account by each host (before the hosts send

each other their MSS values) and how this helps to avoid fragmentation.

-

Host A compares its MSS buffer (16K) and its MTU (1500 - 40 = 1460)

and uses the lower value as the MSS (1460) to send to Host B.

-

Host B receives Host A's send MSS (1460) and compares it to the value

of its outbound interface MTU - 40 (4422).

-

Host B sets the lower value (1460) as the MSS for sending IP

datagrams to Host A.

-

Host B compares its MSS buffer (8K) and its MTU (4462-40 = 4422) and

uses 4422 as the MSS to send to Host A.

-

Host A receives Host B's send MSS (4422) and compares it to the value

of its outbound interface MTU -40 (1460).

-

Host A sets the lower value (1460) as the MSS for sending IP

datagrams to Host B.

1460 is the value chosen by both hosts as the send MSS for each other.

Often the send MSS value will be the same on each end of a TCP connection.

In Scenario 2, fragmentation does not occur at the endpoints of a TCP

connection because both outgoing interface MTUs are taken into account by the

hosts. Packets can still become fragmented in the network between Router A and

Router B if they encounter a link with a lower MTU than that of either hosts'

outbound interface.

TCP MSS as described above takes care of fragmentation at the two endpoints of a TCP connection, but it doesn't handle the case where there is a smaller MTU link in the middle between these two endpoints. PMTUD was developed to avoid fragmentation in the path between the endpoints. It is used to dynamically determine the lowest MTU along the path from a packet's source to its destination.

Note: PMTUD is only supported by TCP. UDP and other protocols do not support it. If PMTUD is enabled on a host, and it almost always is, all TCP/IP packets from the host will have the DF bit set.

When a host sends a full MSS data packet with the DF bit set, PMTUD works by reducing the send MSS value for the connection if it receives information that the packet would require fragmentation. A host usually "remembers" the MTU value for a destination by creating a "host" (/32) entry in its routing table with this MTU value.

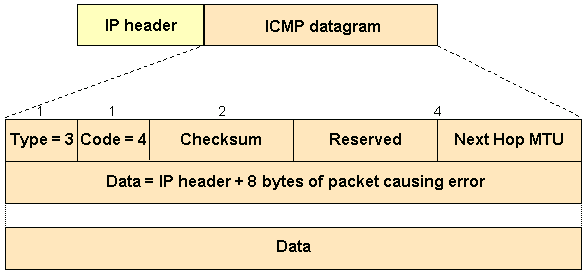

If a router tries to forward an IP datagram, with the DF bit set, onto a link that has a lower MTU than the size of the packet, the router will drop the packet and return an Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) "Destination Unreachable" message to the source of this IP datagram, with the code indicating "fragmentation needed and DF set" (type 3, code 4). When the source station receives the ICMP message, it will lower the send MSS, and when TCP retransmits the segment, it will use the smaller segment size.

Here is an example of an ICMP "fragmentation needed and DF set" message that you might see on a router after turning on the debug ip icmp command:

ICMP: dst (10.10.10.10) frag. needed and DF set

unreachable sent to 10.1.1.1

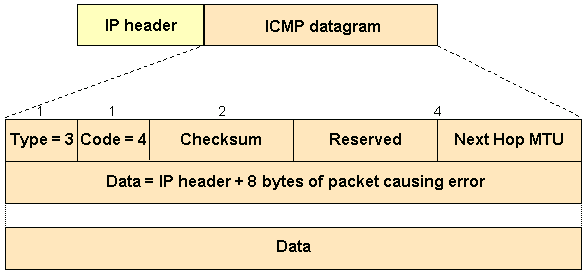

The diagram below shows the format of ICMP header of a "fragmentation needed and DF set" "Destination Unreachable" message.

Per

RFC 1191

, a router returning an ICMP message indicating "fragmentation needed and DF set" should include the MTU of that next-hop network in the low-order 16 bits of the ICMP additional header field that is labeled "unused" in the ICMP specification

RFC 792

.

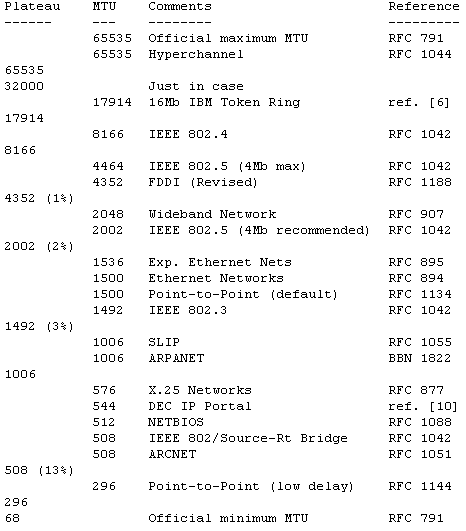

Early implementations of RFC 1191 did not supply the next hop MTU information. Even when this information was supplied, some hosts ignore it. For this case, RFC 1191 also contains a table that lists the suggested values by which the MTU should be lowered during PMTUD. It is used by hosts to arrive more quickly at a reasonable value for the send MSS.

PMTUD is done continually on all packets because the path between sender and receiver can change dynamically. Each time a sender receives a "Can't Fragment" ICMP messages it will update the routing information (where it stores the PMTUD).

Two possible things can happen during PMTUD:

The packet can get all the way to the receiver without being fragmented.

Note: In order for a router to protect the CPU against DoS attacks, it throttles the number of ICMP unreachable messages that it would send, to two per second. Therefore, in this context, if you have a network scenario in which you expect that the router would need to respond with more than two ICMP (code = 3, type = 4) per second (can be different hosts), you would want to disable the throttling of ICMP messages with the no ip icmp rate-limit unreachable [df] interface command.

The sender can get ICMP "Can't Fragment" messages from any (or every) hop along the path to the receiver.

PMTUD is done independently for both directions of a TCP flow. There may be cases where PMTUD in one direction of a flow triggers one of the end stations to lower the send MSS and the other end station keeps the original send MSS because it never sent an IP datagram large enough to trigger PMTUD.

A good example of this is the HTTP connection depicted below in Scenario 3. The TCP client is sending small packets and the server is sending large packets. In this case, only the servers large packets (greater than 576 bytes) will trigger PMTUD. The client's packets are small (less than 576 bytes) and will not trigger PMTUD because they do not require fragmentation to get across the 576 MTU link.

Scenario 3

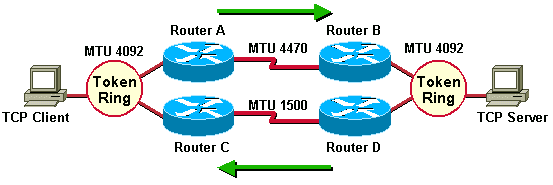

Scenario 4 shows an asymmetric routing example where one of the paths has a smaller minimum MTU than the other. Asymmetric routing occurs when different paths are taken for sending and receiving data between two endpoints. In this scenario, PMTUD will trigger the lowering of the send MSS only in one direction of a TCP flow. The traffic from the TCP client to the server flows through Router A and Router B, whereas the return traffic coming from the server to the client flows through Router D and Router C. When the TCP server sends packets to the client, PMTUD will trigger the server to lower the send MSS because Router D must fragment the 4092 byte packets before it can send them to Router C.

The client, on the other hand, will never receive an ICMP "Destination Unreachable" message with the code indicating "fragmentation needed and DF set" because Router A does not have to fragment packets when sending to the server through Router B.

Scenario 4

Note: The ip tcp path-mtu-discovery command is used to enable TCP MTU path discovery for TCP connections initiated by routers (BGP and Telnet for example).

There are three things that can break PMTUD, two of which are uncommon and one of which is common.

A router can drop a packet and not send an ICMP message. (Uncommon)

A router can generate and send an ICMP message but the ICMP message gets blocked by a router or firewall between this router and the sender. (Common)

A router can generate and send an ICMP message, but the sender ignores the message. (Uncommon)

The first and last of the three bullets above are uncommon and are usually the result of an error, but the middle bullet describes a common problem. People that implement ICMP packet filters tend to block all ICMP message types rather than only blocking certain ICMP message types. A packet filter can block all ICMP message typesexcept those that are "unreachable" or "time-exceeded." The success or failure of PMTUD hinges upon ICMP unreachable messages getting through to the sender of a TCP/IP packet. ICMP time-exceeded messages are important for other IP issues. An example of such a packet filter, implemented on a router is shown below.

access-list 101 permit icmp any any unreachable

access-list 101 permit icmp any any time-exceeded

access-list 101 deny icmp any any

access-list 101 permit ip any any

There are other techniques that can be used to help alleviate the problem of ICMP being completely blocked.

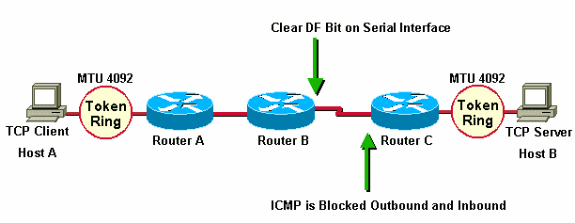

In Scenario 5 below, Router A and Router B are in the same administrative domain. Router C is inaccessible and is blocking ICMP, so PMTUD is broken. A workaround for this situation is to clear the DF bit in both directions on Router B to allow fragmentation. This can be done using policy routing. The syntax to clear the DF bit is available in Cisco IOS® Software Release 12.1(6) and later.

interface serial0

...

ip policy route-map clear-df-bit

route-map clear-df-bit permit 10

match ip address 111

set ip df 0

access-list 111 permit tcp any any

Another option is to change the TCP MSS option value on SYN packets that traverse the router (available in Cisco IOS 12.2(4)T and later). This reduces the MSS option value in the TCP SYN packet so that it's smaller than the value (1460) in the ip tcp adjust-mss command. The result is that the TCP sender will send segments no larger than this value. The IP packet size will be 40 bytes larger (1500) than the MSS value (1460 bytes) to account for the TCP header (20 bytes) and the IP header (20 bytes).

You can adjust the MSS of TCP SYN packets with the ip tcp adjust-mss command. The following syntax will reduce the MSS value on TCP segments to 1460. This command effects traffic both inbound and outbound on interface serial0.

int s0

ip tcp adjust-mss 1460

IP fragmentation issues have become more widespread since IP tunnels have become more widely deployed. The reason that tunnels cause more fragmentation is because the tunnel encapsulation adds "overhead" to the size a packet. For example, adding Generic Router Encapsulation (GRE) adds 24 bytes to a packet, and after this increase the packet may need to be fragmented because it is larger then the outbound MTU. In a later section of this document, you will see examples of the kinds of problems that can arise with tunnels and IP fragmentation.

PMTUD is needed in network situations where intermediate links have smaller MTUs than the MTU of the end links. Some common reasons for the existence of these smaller MTU links are:

Token Ring (or FDDI)-connected end hosts with an Ethernet connection between them. The Token Ring (or FDDI) MTUs at the ends are greater then the Ethernet MTU in the middle.

PPPoE (often used with ADSL) needs 8 bytes for its header. This reduces the effective MTU of the Ethernet to 1492 (1500 - 8).

Tunneling protocols like GRE, IPsec, and L2TP also need space for their respective headers and trailers. This also reduces the effective MTU of the outgoing interface.

In the following sections we will study the impact of PMTUD where a tunneling protocol is used somewhere between the two end hosts. Of the three cases above this case is the most complex, covering all of the issues that you might see in the other cases.

A tunnel is a logical interface on a Cisco router that provides a way to encapsulate passenger packets inside a transport protocol. It is an architecture designed to provide the services to implement a point-to-point encapsulation scheme. Tunneling has the following three primary components:

Passenger protocol (AppleTalk, Banyan VINES, CLNS, DECnet, IP, or IPX)

Carrier protocol - One of the following encapsulation protocols:

GRE - Cisco's multiprotocol carrier protocol. See

RFC 2784

and

RFC 1701

for more information.

IP in IP tunnels - See

RFC 2003

for more information.

Transport protocol - The protocol used to carry the encapsulated protocol

The packets below illustrate the IP tunneling concepts where GRE is the encapsulation protocol and IP is the transport protocol. The passenger protocol is also IP. In this case, IP is both the transport and the passenger protocol.

Normal Packet

Tunnel Packet

IP is the transport protocol.

GRE is the encapsulation protocol.

IP is the passenger protocol.

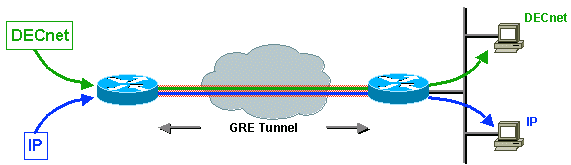

The next example shows the encapsulation of IP and DECnet as passenger protocols with GRE as the carrier. This illustrates the fact that the carrier protocol can encapsulate multiple passenger protocols.

A network administrator might consider tunneling in a situation where there are two discontiguous non-IP networks separated by an IP backbone. If the discontiguous networks are running DECnet, the administrator may not want to connect them together by configuring DECnet in the backbone. The administrator may not want to permit DECnet routing to consume backbone bandwidth because this could interfere with the performance of the IP network.

A viable alternative is to tunnel DECnet over the IP backbone. Tunneling encapsulates the DECnet packets inside IP, and sends them across the backbone to the tunnel endpoint where the encapsulation is removed and the DECnet packets can be routed it their destination via DECnet.

Encapsulating traffic inside another protocol provides the following advantages:

The endpoints are using private addresses (

RFC 1918

) and the backbone does not support routing these addresses.

Allow virtual private networks (VPNs) across WANs or the Internet.

Join together discontiguous multiprotocol networks over a single-protocol backbone.

Encrypt traffic over the backbone or Internet.

For the rest of the document we will use IP as the passenger protocol and IP as the transport protocol.

The following are considerations when tunneling.

Fast switching of GRE tunnels was introduced in Cisco IOS Release 11.1 and CEF switching was introduced in version 12.0. CEF switching for multipoint GRE tunnels was introduced in version 12.2(8)T. Encapsulation and de-capsulation at tunnel endpoints were slow operations in earlier versions of IOS when only process switching was supported.

There are security and topology issues when tunneling packets. Tunnels can bypass access control lists (ACLs) and firewalls. If you tunnel through a firewall, you basically bypass the firewall for whatever passenger protocol you are tunneling. Therefore it is recommended to include firewall functionality at the tunnel endpoints to enforce any policy on the passenger protocols.

Tunneling might create problems with transport protocols that have limited timers (for example, DECnet) because of increased latency

Tunneling across environments with different speed links, like fast FDDI rings and through slow 9600-bps phone lines, may introduce packet reordering problems. Some passenger protocols function poorly in mixed media networks.

Point-to-point tunnels can use up the bandwidth on a physical link. If you are running routing protocols over multiple point-to-point tunnels, keep in mind that each tunnel interface has a bandwidth and that the physical interface over which the tunnel runs has a bandwidth. For example, you would want to set the tunnel bandwidth to 100 Kb if there were 100 tunnels running over a 10 Mb link. The default bandwidth for a tunnel is 9Kb.

Routing protocols may prefer a tunnel over a "real" link because the tunnel might deceptively appear to be a one-hop link with the lowest cost path, although it actually involves more hops and is really more costly than another path. This can be mitigated with proper configuration of the routing protocol. You might want to consider running a different routing protocol over the tunnel interface than the routing protocol running on the physical interface.

Problems with recursive routing can be avoided by configuring appropriate static routes to the tunnel destination. A recursive route is when the best path to the "tunnel destination" is through the tunnel itself. This situation will cause the tunnel interface to bounce up and down. You will see the following error when there is a recursive routing problem.

%TUN-RECURDOWN Interface Tunnel 0

temporarily disabled due to recursive routing

The router has two different PMTUD roles to play when it is the endpoint of a tunnel.

In the first role the router is the forwarder of a host packet. For PMTUD processing, the router needs to check the DF bit and packet size of the original data packet and take appropriate action when necessary.

The second role comes into play after the router has encapsulated the original IP packet inside the tunnel packet. At this stage, the router is acting more like a host with respect to PMTUD and in regards to the tunnel IP packet.

Lets start by looking at what happens when the router is acting in the first role, a router forwarding host IP packets, with respect to PMTUD. This role comes into play before the router encapsulates the host IP packet inside the tunnel packet.

If the router participates as the forwarder of a host packet it will do the following:

Check whether the DF bit is set.

Check what size packet the tunnel can accommodate.

Fragment (if packet is too large and DF bit is not set), encapsulate fragments and send; or

Drop the packet (if packet is too large and DF bit is set) and send an ICMP message to the sender.

Encapsulate (if packet is not too large) and send.

Generically, there is a choice of encapsulation and then fragmentation (sending two encapsulation fragments) or fragmentation and then encapsulation (sending two encapsulated fragments).

Below are some examples that describe the mechanics of IP packet encapsulation and fragmentation and two scenarios that show the interaction of PMTUD and packets traversing example networks.

The first example below shows what happens to a packet when the router (at the tunnel source) is acting in the role of forwarding router. Remember that for PMTUD processing, the router needs to check the DF bit and packet size of the original data packet and take appropriate action. This examples uses GRE encapsulation for the tunnel. As can be seen below, GRE does fragmentation before encapsulation. Later examples show scenarios in which fragmentation is done after encapsulation.

In Example 1 , the DF bit is not set (DF = 0) and the GRE tunnel IP MTU is 1476 (1500 - 24).

Example 1

The forwarding router (at the tunnel source) receives a 1500-byte datagram with the DF bit clear (DF = 0) from the sending host. This datagram is composed of a 20-byte IP header plus a 1480 byte TCP payload.

Because the packet will be too large for the IP MTU after the GRE overhead (24 bytes) is added, the forwarding router breaks the datagram into two fragments of 1476 (20 bytes IP header + 1456 bytes IP payload) and 44 bytes (20 bytes of IP header + 24 bytes of IP payload) so after the GRE encapsulation is added, the packet will not be larger than the outgoing physical interface MTU.

The forwarding router adds GRE encapsulation, which includes a 4-byte GRE header plus a 20-byte IP header, to each fragment of the original IP datagram. These two IP datagrams now have a length of 1500 and 68 bytes, and these datagrams are seen as individual IP datagrams not as fragments.

| IP | GRE | IP0 | 1456 bytes TCP + data |

The tunnel destination router removes the GRE encapsulation from each fragment of the original datagram leaving two IP fragments of lengths 1476 and 24 bytes. These IP datagram fragments will be forwarded separately by this router to the receiving host.

The receiving host will reassemble these two fragments into the original datagram.

Scenario 5 depicts the role of the forwarding router in the context of a network topology.

In the following example, the router is acting in the same role of forwarding router but this time the DF bit is set (DF = 1).

Example 2

The forwarding router at the tunnel source receives a 1500-byte datagram with DF = 1 from the sending host.

Since the DF bit is set, and the datagram size (1500 bytes) is greater than the GRE tunnel IP MTU (1476), the router will drop the datagram and send an "ICMP fragmentation needed but DF bit set" message to the source of the datagram. The ICMP message will alert the sender that the MTU is 1476.

The sending host receives the ICMP message, and when it resends the original data, it will use a 1476-byte IP datagram.

This IP datagram length (1476 bytes) is now equal in value to the GRE tunnel IP MTU so the router adds the GRE encapsulation to the IP datagram.

| IP | GRE | IP | 1456 bytes TCP + data |

The receiving router (at the tunnel destination) removes the GRE encapsulation of the IP datagram and sends it to the receiving host.

Now we can look at what happens when the router is acting in the second role as a sending host with respect to PMTUD and in regards to the tunnel IP packet. Recall that this role comes into play after the router has encapsulated the original IP packet inside the tunnel packet.

Note: By default a router doesn't do PMTUD on the GRE tunnel packets that it generates. The tunnel path-mtu-discovery command can be used to turn on PMTUD for GRE-IP tunnel packets.

Below is an example of what happens when the host is sending IP datagrams that are small enough to fit within the IP MTU on the GRE Tunnel interface. The DF bit in this case can be either set or clear (1 or 0). The GRE tunnel interface does not have the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command configured so the router will not be doing PMTUD on the GRE-IP packet.

Example 3

The forwarding router at the tunnel source receives a 1476-byte datagram from the sending host.

This router encapsulates the 1476-byte IP datagram inside GRE to get a 1500-byte GRE IP datagram. The DF bit in the GRE IP header will be clear (DF = 0). This router then forwards this packet to the tunnel destination.

| IP | GRE | IP | 1456 bytes TCP + data |

Assume there is a router between the tunnel source and destination with a link MTU of 1400. This router will fragment the tunnel packet since the DF bit is clear (DF = 0). Remember that this example fragments the outermost IP, so the GRE, inner IP, and TCP headers will only show up in the first fragment.

| IP0 | GRE | IP | 1352 bytes TCP + data |

The tunnel destination router must reassemble the GRE tunnel packet.

| IP | GRE | IP | 1456 bytes TCP + data |

After the GRE tunnel packet is reassembled, the router removes the GRE IP header and sends the original IP datagram on its way.

The next example shows what happens when the router is acting in the role of a sending host with respect to PMTUD and in regards to the tunnel IP packet. This time the DF bit is set (DF = 1) in the original IP header and we have configured the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command so that the DF bit will be copied from the inner IP header to the outer (GRE + IP) header.

Example 4

The forwarding router at the tunnel source receives a 1476-byte datagram with DF = 1 from the sending host.

This router encapsulates the 1476-byte IP datagram inside GRE to get a 1500-byte GRE IP datagram. This GRE IP header will have the DF bit set (DF = 1) since the original IP datagram had the DF bit set. This router then forwards this packet to the tunnel destination.

Again, assume there is a router between the tunnel source and destination with a link MTU of 1400. This router will not fragment the tunnel packet since the DF bit is set (DF = 1). This router must drop the packet and send an ICMP error message to the tunnel source router, since that is the source IP address on the packet.

The forwarding router at the tunnel source receives this ICMP error message and it will lower the GRE tunnel IP MTU to 1376 (1400 - 24). The next time the sending host retransmits the data in a 1476-byte IP packet, this packet will be too large and this router will send an ICMP error message to the sender with a MTU value of 1376. When the sending host retransmits the data, it will send it in a 1376-byte IP packet and this packet will make it through the GRE tunnel to the receiving host.

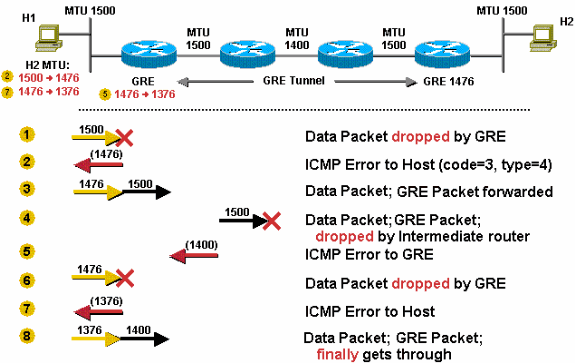

This scenario illustrates GRE fragmentation. Remember that you fragment before encapsulation for GRE, then do PMTUD for the data packet, and the DF bit is not copied when the IP packet is encapsulated by GRE. In this scenario, the DF bit is not set. The GRE tunnel interface IP MTU is, by default, 24 bytes less than the physical interface IP MTU, so the GRE interface IP MTU is 1476.

The the sender sends a 1500-byte packet (20 byte IP header + 1480 bytes of TCP payload).

Since the MTU of the GRE tunnel is 1476, the 1500-byte packet is broken into two IP fragments of 1476 and 44 bytes, each in anticipation of the additional 24 byes of GRE header.

The 24 bytes of GRE header is added to each IP fragment. Now the fragments are 1500 (1476 + 24) and 68 (44 + 24) bytes each.

The GRE + IP packets containing the two IP fragments are forwarded to the GRE tunnel peer router.

The GRE tunnel peer router removes the GRE headers from the two packets.

This router forwards the two packets to the destination host.

The destination host reassembles the IP fragments back into the original IP datagram.

This is scenario a similar to Scenario 5, but this time the DF bit is set. In Scenario 6, the router is configured to do PMTUD on GRE + IP tunnel packets with the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command, and the DF bit is copied from the original IP header to the GRE IP header. If the router receives an ICMP error for the GRE + IP packet, it reduces the IP MTU on the GRE tunnel interface. Again, remember that the GRE Tunnel IP MTU is set to 24 bytes less than the physical interface MTU by default, so the GRE IP MTU here is 1476. Also notice that there is a 1400 MTU link in the GRE tunnel path.

The router receives a 1500-byte packet (20 byte IP header + 1480 TCP payload), and it drops the packet. The router drops the packet because it is larger then the IP MTU (1476) on the GRE tunnel interface.

The router sends an ICMP error to the sender telling it that the next-hop MTU is 1476. The host will record this information, usually as a host route for the destination in its routing table.

The sending host uses a 1476-byte packet size when it resends the data. The GRE router adds 24 bytes of GRE encapsulation and ships out a 1500-byte packet.

The 1500-byte packet cannot traverse the 1400-byte link, so it is dropped by the intermediate router.

The intermediate router sends an ICMP (code = 3, type = 4) to the GRE router with a next-hop MTU of 1400. The GRE router reduces this to 1376 (1400 - 24) and sets an internal IP MTU value on the GRE interface. This change can only be seen when using the debug tunnel command; it cannot be seen in the output from the show ip interface tunnel<#> command.

The next time the host resends the 1476-byte packet, the GRE router will drop the packet, since it is larger then the current IP MTU (1376) on the GRE tunnel interface.

The GRE router will send another ICMP (code = 3, type = 4) to the sender with a next-hop MTU of 1376 and the host will update its current information with new value.

The host again resends the data, but now in a smaller 1376-byte packet, GRE will add 24 bytes of encapsulation and forward it on. This time the packet will make it to the GRE tunnel peer, where the packet will be de-capsulated and sent to the destination host.

Note: If the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command was not configured on the forwarding router in this scenario, and the DF bit was set in the packets forwarded through the GRE tunnel, Host 1 would still succeed in sending TCP/IP packets to Host 2, but they would get fragmented in the middle at the 1400 MTU link. Also the GRE tunnel peer would have to reassemble them before it could decapsulate and forward them on.

The IP Security (IPsec) Protocol is a standards-based method of providing privacy, integrity, and authenticity to information transferred across IP networks. IPsec provides IP network-layer encryption. IPsec lengthens the IP packet by adding at least one IP header (tunnel mode). The added header(s) varies in length depending the IPsec configuration mode but they do not exceed ~58 bytes (Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) and ESP authentication (ESPauth)) per packet.

IPsec has two modes, tunnel mode and transport mode.

Tunnel mode is the default mode. With tunnel mode, the entire original IP packet is protected (encrypted, authenticated, or both) and encapsulated by the IPsec headers and trailers. Then a new IP header is prepended to the packet, specifying the IPsec endpoints (peers) as the source and destination. Tunnel mode can be used with any unicast IP traffic and must be used if IPsec is protecting traffic from hosts behind the IPsec peers. For example, tunnel mode is used with Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) where hosts on one protected network send packets to hosts on a different protected network via a pair of IPsec peers. With VPNs, the IPsec "tunnel" protects the IP traffic between hosts by encrypting this traffic between the IPsec peer routers.

With transport mode (configured with the subcommand, mode transport, on the transform definition), only the payload of the original IP packet is protected (encrypted, authenticated, or both). The payload is encapsulated by the IPsec headers and trailers. The original IP headers remain intact, except that the IP protocol field is changed to be ESP (50), and the original protocol value is saved in the IPsec trailer to be restored when the packet is decrypted. Transport mode is used only when the IP traffic to be protected is between the IPsec peers themselves, the source and destination IP addresses on the packet are the same as the IPsec peer addresses. Normally IPsec transport mode is only used when another tunneling protocol (like GRE) is used to first encapsulate the IP data packet, then IPsec is used to protect the GRE tunnel packets.

IPsec always does PMTUD for data packets and for its own packets. There are IPsec configuration commands to modify PMTUD processing for the IPsec IP packet, IPsec can clear, set, or copy the DF bit from the data packet IP header to the IPsec IP header. This is called the "DF Bit Override Functionality" feature.

Note: You really want to avoid fragmentation after encapsulation when you do hardware encryption with IPsec. Hardware encryption can give you throughput of about 50 Mbs depending on the hardware, but if the IPsec packet is fragmented you loose 50 to 90 percent of the throughput. This loss is because the fragmented IPsec packets are process-switched for reassembly and then handed to the Hardware encryption engine for decryption. This loss of throughput can bring hardware encryption throughput down to the performance level of software encryption (2-10 Mbs).

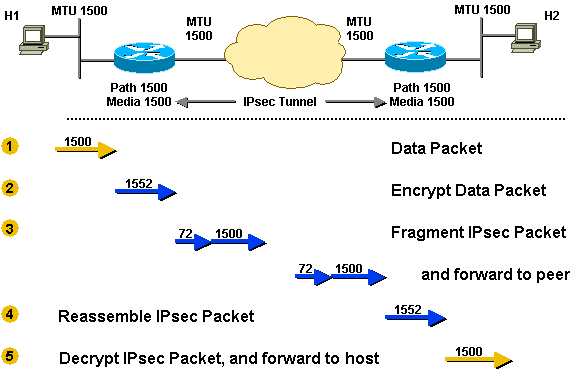

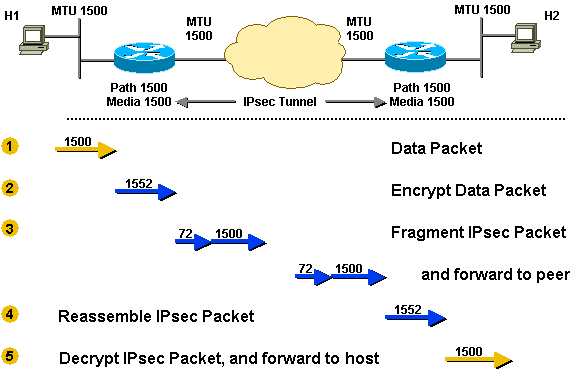

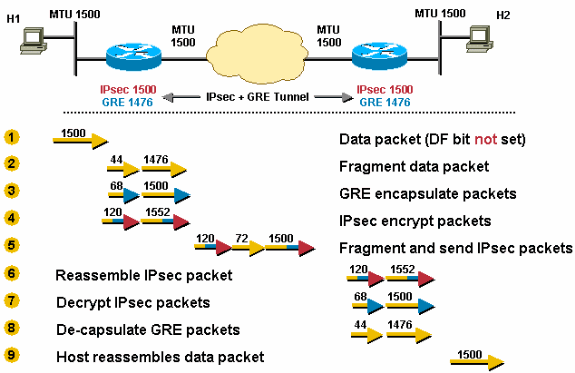

This scenario depicts IPsec fragmentation in action. In this scenario, the MTU along the entire path is 1500. In this scenario, the DF bit is not set.

The router receives a 1500-byte packet (20-byte IP header + 1480 bytes TCP payload) destined for Host 2.

The 1500-byte packet is encrypted by IPsec and 52 bytes of overhead are added (IPsec header, trailer, and additional IP header). Now IPsec needs to send a 1552-byte packet. Since the outbound MTU is 1500, this packet will have to be fragmented.

Two fragments are created out of the IPsec packet. During fragmentation, an additional 20-byte IP header is added for the second fragment, resulting in a 1500-byte fragment and a 72-byte IP fragment.

The IPsec tunnel peer router receives the fragments, strips off the additional IP header and coalesces the IP fragments back into the original IPsec packet. Then IPsec decrypts this packet.

The router then forwards the original 1500-byte data packet to Host 2.

This scenario is similar to Scenario 6 except that in this case the DF bit is set in the original data packet and there is a link in the path between the IPsec tunnel peers that has a lower MTU than the other links. This scenario demonstrates how the IPsec peer router performs both PMTUD roles, as described in the

The Router as a PMTUD Participant at the Endpoint of a Tunnel section.

You will see in this scenario how the IPsec PMTU changes to a lower value as the result of the need for fragmentation. Remember that the DF bit is copied from the inner IP header to the outer IP header when IPsec encrypts a packet. The media MTU and PMTU values are stored in the IPsec Security Association (SA). The media MTU is based on the MTU of the outbound router interface and the PMTU is based on the minimum MTU seen on the path between the IPsec peers. Remember that IPsec encapsulates/encrypts the packet before it attempts to fragment it.

The router receives a 1500-byte packet and drops it because the IPsec overhead, when added, will make the packet larger then the PMTU (1500).

The router sends an ICMP message to Host 1 telling it that the next-hop MTU is 1442 (1500 - 58 = 1442). This 58 bytes is the maximum IPsec overhead when using IPsec ESP and ESPauth. The real IPsec overhead may be as much as 7 bytes less then this value. Host 1 records this information, usually as a host route for the destination (Host 2), in its routing table.

Host 1 lowers its PMTU for Host 2 to 1442, so Host 1 will send smaller (1442 byte) packets when it retransmits the data to Host 2. The router receives the 1442-byte packet and IPsec adds 52 bytes of encryption overhead so the resulting IPsec packet is 1496 bytes. Because this packet has the DF bit set in its header it gets dropped by the middle router with the 1400-byte MTU link.

The middle router that dropped the packet sends an ICMP message to the sender of the IPsec packet (the first router) telling it that the next-hop MTU is 1400 bytes. This value is recorded in the IPsec SA PMTU.

The next time Host 1 retransmits the 1442-byte packet (it didn't receive an acknowledgment for it), the IPsec will drop the packet. Again the router will drop the packet because the IPsec overhead, when added to the packet, will make it larger then the PMTU (1400).

The router sends an ICMP message to Host 1 telling it that the next-hop MTU is now 1342. (1400 - 58 = 1342). Host 1 will again record this information.

When Host 1 again retransmits the data, it will use the smaller size packet (1342). This packet will not require fragmentation and will make it through the IPsec tunnel to Host 2.

More complex interactions for fragmentation and PMTUD occur when IPsec is used to encrypt GRE tunnels. IPsec and GRE are combined in this manner because IPsec doesn't support IP multicast packets, which means that you cannot run a dynamic routing protocol over the IPsec VPN Network. GRE tunnels do support multicast, so a GRE tunnel can be used to first encapsulate the dynamic routing protocol multicast packet in a GRE IP unicast packet, that can then be encrypted by IPsec. When doing this, IPsec is often deployed in transport mode on top of GRE because the IPsec peers and the GRE tunnel endpoints (the routers) are the same, and transport-mode will save 20 bytes of IPsec overhead.

One interesting case is when an IP packet has been split into two fragments and encapsulated by GRE. In this case IPsec will see two independent GRE + IP packets. Often in a default configuration one of these packets will be large enough that it will need to be fragmented after it has been encrypted. The IPsec peer will have to reassemble this packet before decryption. This "double fragmentation" (once before GRE and again after IPsec) on the sending router increases latency and lowers throughput. Also, reassembly is process-switched, so there will be a CPU hit on the receiving router whenever this happens.

This situation can be avoided by setting the "ip mtu" on the GRE tunnel interface low enough to take into account the overhead from both GRE and IPsec (by default the GRE tunnel interface "ip mtu" is set to the outgoing real interface MTU - GRE overhead bytes).

The following table lists the suggested MTU values for each tunnel/mode combination assuming the outgoing physical interface has an MTU of 1500.

| Tunnel Combination | Specific MTU Needed | Recommended MTU |

| GRE + IPsec (Transport mode) | 1440 bytes | 1400 bytes |

| GRE + IPsec (Tunnel mode) | 1420 bytes | 1400 bytes |

Note: The MTU value of 1400 is recommended because it covers the most common GRE + IPsec mode combinations. Also, there is no discernable downside to allowing for an extra 20 or 40 bytes overhead. It is easier to remember and set one value and this value covers almost all scenarios.

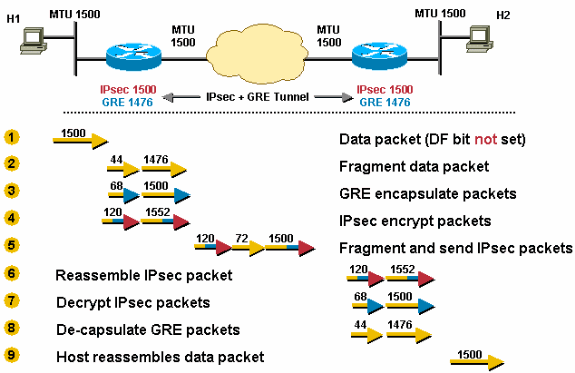

IPsec is deployed on top of GRE. The outgoing physical MTU is 1500, the IPsec PMTU is 1500, and the GRE IP MTU is 1476 (1500 - 24 = 1476). Because of this, TCP/IP packets will be fragmented twice, once before GRE and once after IPsec. The packet will be fragmented before GRE encapsulation and one of these GRE packets will be fragmented again after IPsec encryption.

Configuring "ip mtu 1440" (IPsec Transport mode) or "ip mtu 1420" (IPsec Tunnel mode) on the GRE tunnel would remove the possibility of double fragmentation in this scenario.

The router receives a 1500-byte datagram.

Before encapsulation, GRE fragments the 1500-byte packet into two pieces, 1476 (1500 - 24 = 1476) and 44 (24 data + 20 IP header) bytes.

GRE encapsulates the IP fragments, which adds 24 bytes to each packet. This results in two GRE + IPsec packets of 1500 (1476 + 24 = 1500) and 68 (44 + 24) bytes each.

IPsec encrypts the two packets, adding 52 byes (IPsec tunnel-mode) of encapsulation overhead to each, to give a 1552-byte and a 120-byte packet.

The 1552-byte IPsec packet is fragmented by the router because it is larger then the outbound MTU (1500). The 1552-byte packet is split into pieces, a 1500-byte packet and a 72-byte packet (52 bytes "payload" plus an additional 20-byte IP header for the second fragment). The three packets 1500-byte, 72-byte, and 120-byte packets are forwarded to the IPsec + GRE peer.

The receiving router reassembles the two IPsec fragments (1500 bytes and 72 bytes) to get the original 1552-byte IPsec + GRE packet. Nothing needs to be done to the 120-byte IPsec + GRE packet.

IPsec decrypts both 1552-byte and 120-byte IPsec + GRE packets to get 1500-byte and 68-byte GRE packets.

GRE decapsulates the 1500-byte and 68-byte GRE packets to get 1476-byte and 44-byte IP packet fragments. These IP packet fragments are forwarded to the destination host.

Host 2 reassembles these IP fragments to get the original 1500-byte IP datagram.

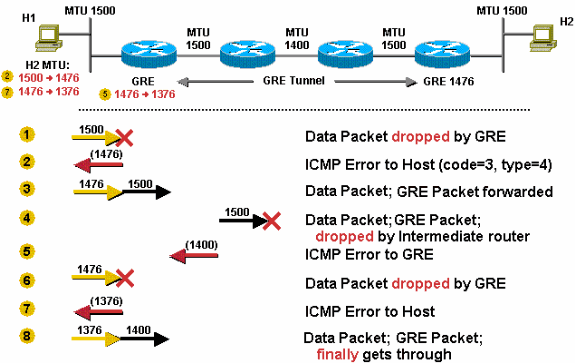

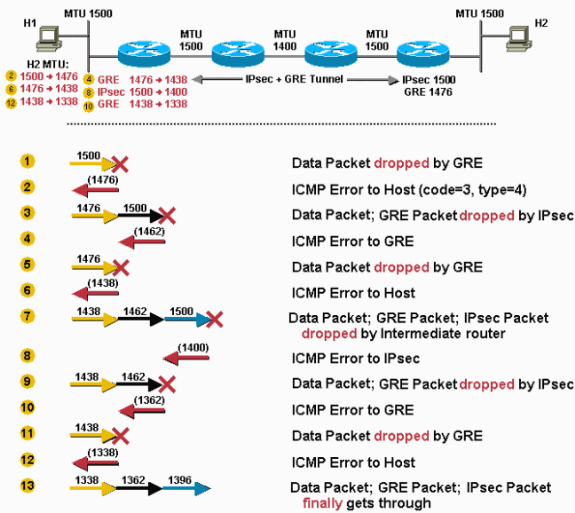

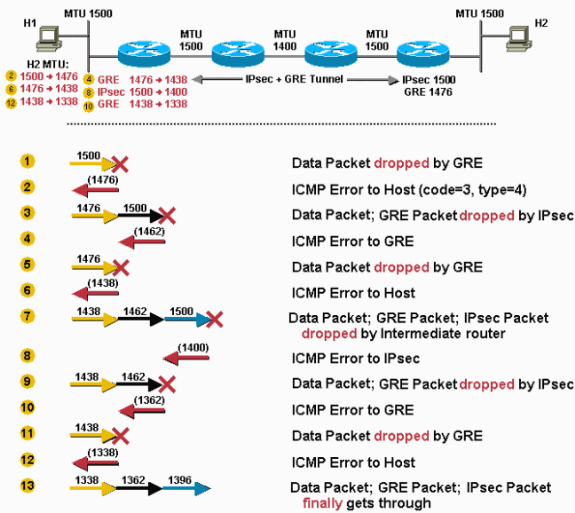

Scenario 10 is similar to Scenario 8 except there is a lower MTU link in the tunnel path. This is a "worst case" scenario for the first packet sent from Host 1 to Host 2. After the last step in this scenario, Host 1 sets the correct PMTU for Host 2 and all is well for the TCP connections between Host 1 and Host 2. TCP flows between Host 1 and other hosts (reachable via the IPsec + GRE tunnel) will only have to go through the last three steps of Scenario 10.

In this scenario, the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command is configured on the GRE tunnel and the DF bit is set on TCP/IP packets originating from Host 1.

The router receives a 1500-byte packet. This packet is dropped by GRE because GRE cannot fragment or forward the packet because the DF bit is set, and the packet size exceeds the outbound interface "ip mtu" after adding the GRE overhead (24 bytes).

The router sends an ICMP message to Host 1 letting it know that the next-hop MTU is 1476 (1500 - 24 = 1476).

Host 1 changes its PMTU for Host 2 to 1476 and sends the smaller size when it retransmits the packet. GRE encapsulates it and hands the 1500-byte packet to IPsec. IPsec drops the packet because GRE has copied the DF bit (set) from the inner IP header, and with the IPsec overhead (maximum 38 bytes), the packet is too large to forward out the physical interface.

IPsec sends an ICMP message to GRE indicating that the next-hop MTU is 1462 bytes (since a maximum 38 bytes will be added for encryption and IP overhead). GRE records the value 1438 (1462 - 24) as the "ip mtu" on the tunnel interface.

Note: This change in value is stored internally and cannot be seen in the output of the show ip interface tunnel<#> command. You will only see this change if you turn use the debug tunnel command.

The next time Host 1 retransmits the 1476-byte packet, GRE drops it.

The router sends an ICMP message to Host 1 indicating that 1438 is the next-hop MTU.

Host 1 lowers the PMTU for Host 2 and retransmits a 1438-byte packet. This time, GRE accepts the packet, encapsulates it, and hands it off to IPsec for encryption. The IPsec packet is forwarded to the intermediate router and dropped because it has an outbound interface MTU of 1400.

The intermediate router sends an ICMP message to IPsec telling it that the next-hop MTU is 1400. This value is recorded by IPsec in the PMTU value of the associated IPsec SA.

When Host 1 retransmits the 1438-byte packet, GRE encapsulates it and hands it to IPsec. IPsec drops the packet because it has changed its own PMTU to 1400.

IPsec sends an ICMP error to GRE indicating that the next-hop MTU is 1362, and GRE records the value 1338 internally.

When Host 1 retransmits the original packet (because it did not receive an acknowledgment), GRE drops it.

The router sends an ICMP message to Host 1 indicating the next-hop MTU is 1338 (1362 - 24 bytes). Host 1 lowers its PMTU for Host 2 to 1338.

Host 1 retransmits a 1338-byte packet and this time it can finally get all the way through to Host 2.

Configuring the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command on a tunnel interface can help GRE and IPsec interaction when they are configured on the same router. Remember that without the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command configured, the DF bit would always be cleared in the GRE IP header. This allows the GRE IP packet to be fragmented even though the encapsulated data IP header had the DF bit set, which normally wouldn't allow the packet to be fragmented.

If the tunnel path-mtu-discovery command is configured on the GRE tunnel interface, the following will happen.

GRE will copy the DF bit from the data IP header to the GRE IP header.

If the DF bit is set in the GRE IP header and the packet will be "too large" after IPsec encryption for the IP MTU on the physical outgoing interface, then IPsec will drop the packet and notify the GRE tunnel to reduce its IP MTU size.

IPsec does PMTUD for its own packets and if the IPsec PMTU changes (if it is reduced), then IPsec doesn't immediately notify GRE, but when another "too large" packet comes thorough, then the process in step 2 occurs.

GRE's IP MTU is now smaller, so it will drop any data IP packets with the DF bit set that are now too large and send an ICMP message to the sending host.

The tunnel path-mtu-discovery command helps the GRE interface set its IP MTU dynamically, rather than statically with the ip mtu command. It is actually recommended that both commands are used. The ip mtucommand is used to provide room for the GRE and IPsec overhead relative to the local physical outgoing interface IP MTU. The tunnel path-mtu-discovery command allows the GRE tunnel IP MTU to be further reduced if there is a lower IP MTU link in the path between the IPsec peers.

Below are some of the things you can do if you are having problems with PMTUD in a network where there are GRE + IPsec tunnels configured.

The following list begins with the most desirable solution.

Fix the problem with PMTUD not working, which is usually caused by a router or firewall blocking ICMP.

Use the ip tcp adjust-mss command on the tunnel interfaces so that the router will reduce the TCP MSS value in the TCP SYN packet. This will help the two end hosts (the TCP sender and receiver) to use packets small enough so that PMTUD is not needed.

Use policy routing on the ingress interface of the router and configure a route map to clear the DF bit in the data IP header before it gets to the GRE tunnel interface. This will allow the data IP packet to be fragmented before GRE encapsulation.

Increase the "ip mtu" on the GRE tunnel interface to be equal to the outbound interface MTU. This will allow the data IP packet to be GRE encapsulated without fragmenting it first. The GRE packet will then be IPsec encrypted and then fragmented to go out the physical outbound interface. In this case you would not configure tunnel path-mtu-discovery command on the GRE tunnel interface. This can dramatically reduce the throughput because IP packet reassembly on the IPsec peer is done in process-switching mode.

and implemented in recent TCP/IP stacks. This algorithm attempts to discover the largest IP datagram that can be sent without fragmentation through an IP path and maximizes data transfer throughput.

and implemented in recent TCP/IP stacks. This algorithm attempts to discover the largest IP datagram that can be sent without fragmentation through an IP path and maximizes data transfer throughput.

. A "1" enables discovery while a "0" disables it. The default is 1.

. A "1" enables discovery while a "0" disables it. The default is 1.